Overview

The waterways of the Corangamite region are diverse and complex ecosystems and the ‘lifeblood’ of many communities. They have unique environmental values, providing habitat for native fish, invertebrates and water birds, while supporting extensive vegetation communities. They also have strong cultural and historic significance, are a focal point for recreation and tourism, and their catchments provide our community with water for drinking, irrigation and industry.

There are approximately 19,600 km of waterways in the Corangamite Region. The Otway National Park contains some of the most naturally intact waterways in Australia, featuring good water quality. In contrast, other waterways (such as the Moorabool and Woady Yaloak rivers) have experienced significant degradation and now exhibit poor water quality.

Waterways act as connections between catchments, aquifers, riparian zones (streamside environments), estuaries, and the marine environment, and their health and functioning can substantially impact upon these dependent ecosystems. Since European settlement, human interactions with waterways, through changes in and intensification of land use, as well as modification of the natural environment, have led to altered water flows and a decline in waterway health.

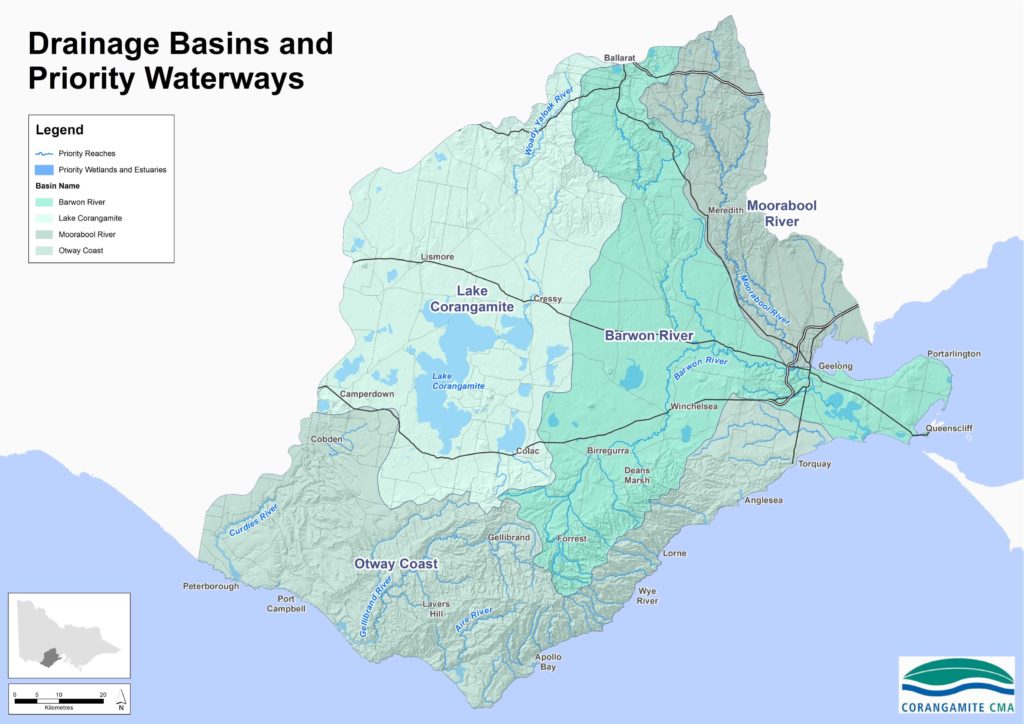

The Corangamite region consists of four drainage basins that reflect the geology and landscape evolution of the region. These basins are:

Moorabool Basin – includes the Moorabool River, which is the major river system flowing through the east of the region, and Hovells Creek, a small creek system that rises in the southern foothills of the You Yangs and flows into Corio Bay.

Barwon Basin – includes the Barwon River, which rises in the northern slopes of the Otway Range, and the Leigh River, which begins in the central Victorian uplands around Ballarat, joining the Barwon River at Inverleigh.

Lake Corangamite Basin – a landlocked system that includes the Woady Yaloak River and a number of small ephemeral creeks feeding Lake Corangamite, as well as other significant lakes and wetlands.

Otway Coast Basin– includes the Curdies River, which occupies the western section, the Gellibrand, Aire, and numerous small coastal streams which occupy the central Otways, and the Erskine River, Spring and Thompson creeks, which flow through the eastern section.

Management of the region’s waterways is guided by the Corangamite Waterway Strategy 2014-2022 which sets out a plan for the conservation and restoration of all water bodies in the region (including wetlands and estuaries). Waterway management in Corangamite has a strong community-based program history, through Landcare, WaterWatch and EstuaryWatch initiatives. These volunteer initiatives are especially important, given that 78% of the region is under private ownership.

The Corangamite Waterway Strategy focuses on the management, maintenance and improvement of all waterways within the region, recognising the importance of waterways as a connection between catchments, aquifers, streamside vegetation, estuaries and the marine environment, at the same time acknowledging the strong influence land use and catchment condition have in this context. Integrated catchment management also brings together people, ideas and practices across land tenure boundaries and a range of natural resource management themes.

The Corangamite Regional Floodplain Management Strategy outlines how the ecological and cultural values of the natural floodplains can be protected while also managing the risks to life, property and assets associated with flooding. Corangamite flood mapping can be accessed on, Digital Twin Victoria the authoritative and comprehensive digital model of our state.

Given the importance of waterways to the Wadawurrung and Eastern Maar Traditional Owners, it is important that they have a strong voice in how they are managed. Opportunities for management and use of water by Wadawurrung and Eastern Maar people for cultural, economic, tourism and business opportunities need to be explored and implemented. Developing enduring partnerships with the Wadawurrung and Eastern Maar people will help to ensure their voice is not only heard but used to develop and implement jointly agreed goals for priority waterways in the region.

Waterways also support a range of human “amenity” values related to the quality of the sensory visitor experience. The amenity values of waterways are defined by the experience of naturalness, escape and safety and the built infrastructure designed to enhance these experiences. For instance waterways support many recreational activities such as walking, cycling, boating and cultural heritage education. Visitors to waterways have different expectations on the types of recreational activities catered for, the feeling of naturalness that they would like to see and the absence or presence of facilities, signage and access to various river lengths. Therefore, planning waterway amenity should be driven by community expectations, the existing natural features of each waterway and the current infrastructure and recreational activities catered for. Careful planning is required to ensure that along any one waterway, there are a variety of amenity values catering for different user experiences.

Assessment of current condition and trends

Waterways support a range of important values such as water supply to industry, agriculture and urban centres, fishing, swimming and boating, as well as important habitat for native plants and animals. Many of these waterway values depend on the environmental condition of the river channel. For example, boat ramps rely on the stability and composition of the bed and banks, while the best swimming spots are often within deep, natural pools. Stable bed and banks of the river channel help to improve the quality of water that flows to downstream users. Fishing success depends on healthy populations of fish species which, in turn, rely on the availability and condition of habitat in the river channel.

Waterways act as connections between catchments, aquifers, riparian zones (streamside environments) estuaries and the marine environment and their health and functioning can substantially impact upon these dependent ecosystems.

The 2010 Index of Stream Condition report for the Corangamite region shows stream condition varies. The majority of stream length in good and excellent condition was clustered in the heavily forested Otway Coast Basin (44% of stream length). Only 11% of the Corangamite region’s waterway length was found to be in excellent condition, and a further 7% in good condition. In contrast, there were no streams in good or excellent condition in the highly modified Moorabool basin. The majority of stream lengths in the Barwon, Moorabool, and Corangamite basins were in moderate or poor condition. All streams within or adjacent to major urban centres (Geelong and Ballarat) were assessed as being in very poor condition.

In December 2020 the Long Term Water Resource Assessment for southern Victoria was released by the State Government. One of the main objectives of this work was to determine if long-term water availability had declined and if there were changes in how water was shared between the environment and consumptive uses. The study estimated the following reductions in water availability since the previous Sustainable Water Strategies (2011 for the Western Sustainable Water Strategy that included the Gellibrand, and 2006 for the Central Sustainable Water Strategy that includes the Barwon Moorabool and Leigh):

1) Barwon Basin: Current: 232.5 GL/yr; Historical: 262.1 GL/year (11% reduction)

2) Moorabool Basin: Current 92.2 GL/yr; Historical: 114.7 GL/year (20% reduction)

3) Lake Corangamite Basin: Current: 54.7 GL/year; Historical: 69.4 GL/year (21% reduction)

4) Otway Coast Basin: Current: 563.8 GL/year; Historical: 589.6 GL/yr (4% reduction)

The Long Term Water Resource Assessment also showed that for the Moorabool and Barwon Basins, the reduction in water availability has fallen disproportionally on the environment relative to consumptive use. The Central and Gippsland Sustainable Water Strategy currently in development will set out the Victorian Government’s plan for a climate resilient future – a future where we have the water we need for our economic, environmental, social and cultural purposes.

Victoria’s water resources are managed under a water entitlement framework which balances demands for water for both consumptive and environmental purposes. Different entitlements are necessary depending on where and how water is taken, and what it is then used for. Many of the region’s major waterways are used to extract water for a variety of uses under water entitlements of various forms.

Bulk entitlements and environmental entitlements are legal rights to water granted by the Minister for Water under the Water Act 1989. They provide the right to take or store a volume of water, subject to a range of conditions. Bulk entitlements are held by specified authorities, such as water corporations, while environmental entitlements are held by the Victorian Environmental Water Holder. The Corangamite CMA currently manages three formal environmental entitlements in the Moorabool River, Lower Barwon Wetlands, and the Upper Barwon River on behalf of the Victorian Environmental Water Holder (VEWH). This involves development of ‘seasonal water proposals’ outlining the recommended timing and magnitude of allocated environmental water flows for maximum environmental and social benefit. The seasonal water proposals are then used by VEWH to inform an annual and statewide ‘seasonal watering plan’ which is then implemented by the various water storage managers.

Water quality in the catchment is monitored by dedicated volunteers through the Corangamite Waterwatch Program, which has been running since 1995. Since then, numerous citizen scientists have been actively involved in local waterway monitoring and onground activities. Data collected from waterways is, in many instances, the only data collected at these particular sites. There are currently 62 active volunteers monitoring 125 active sites in the Corangamite region. In addition, schools have been engaged with the freshwater education program River Detectives. The Corangamite Waterwatch Program monitors the following water quality parameters:

- Electrical Conductivity

- pH

- Temperature

- Turbidity

- Reactive Phosphorus

- Dissolved Oxygen

Habitat surveys and aquatic macroinvertebrate (water bug) surveys are also performed at many Waterwatch sites. Assessment of macroinvertebrate communities enables an ecological assessment of the waterway health.

Although the physical health of a waterway can be defined by various measurable parameters described above, the sensory visitor experience or ‘amenity’ is more subjective. For this strategy, case studies of the Barwon River through Geelong to the estuary at Barwon Heads, the Moorabool River downstream of Meredith and the Yarrowee River through Ballarat were chosen to map current amenity based on the ‘naturalness’ and supporting infrastructure (see Regional maps). In addition, desired amenity was also mapped for the Yarrowee River through Ballarat based on the City of Ballarat’s Yarrowee River Masterplan (see Regional maps). Comparisons between actual and desirable amenity provides opportunity to develop actions to address the difference via projects and plans such as the Barwon River Parklands Project and the Yarrowee River Corridor Masterplan. The case study reaches were chosen because they traverse a variety of urban and rural settings. In time, the method used in the case study areas will be applied to other main waterways in the region.

Major threats and drivers of change

Waterways are a focal point for many cities and towns in the Corangamite region, often providing important community benefits, and contributing to the identity of a place. Waterways near urban areas are often highly modified, which can impact significantly on their health. They are subject to increasing pressure from urban development, which leads to a greater proportion of impervious surfaces that increase runoff of stormwater, changing the intensity and frequency of flows that would otherwise be gradually released through soil and vegetation.

As the population of the Corangamite region is one of the fastest growing areas in Victoria, this is expected to further increase pressures, given increasing associated demand for water supply, as well as impacts from further urban development. With population growth and increased urbanisation comes a greater demand for sensory escape to the natural world with a heightened need to conserve and build on the natural features of waterways and develop infrastructure to enhance the visitor experience.

Climate change presents a major threat to the waterways of the region. There will likely be a decrease in the number and area of permanent and seasonal wetlands and an increase in the number and area of intermittent wetlands. It will also have a major impact on river flows in both extent and timing. Recent estimates of the likely percentage reduction in average flows over the next 50 years are provided in the climate change page of this strategy (source: DELWP water availability climate change guidelines). The most vulnerable waterways in the region are those in the Otway Ranges, especially those flowing southwards into the Southern Ocean. These waterways have small, confined catchments, are unregulated, rely on high levels of rainfall and are relatively short in length. Reduced runoff into these rivers and streams will have a detrimental impact on these systems.

Extreme events such as fires and floods also present a major threat to the region’s waterways. The adverse effects of floods and bushfire on waterways are primarily related to erosion and mobilisation of sediment, damage to native riparian vegetation and acceleration of the spread of invasive species. Invasive species in waterways and along riparian land are an increasing threat to the health of rivers, estuaries and wetlands in the Corangamite region. Invasive plants such as willows, gorse and blackberry as well as phalaris and tall wheat grass are well established in the region and can be costly to control. Effective management of weed species needs to consider not only the physical removal of the weed, but also eliminating the source of dispersal in any system, which often extends beyond the limits of a single waterway.

Activities on the land upstream, surrounding or adjacent to waterways (e.g. land clearing, cropping, installation of farm dams, forestry, and intensive animal industries), can have a significant effect on waterway condition through changed water regimes, erosion or water quality impacts from salinity, sediment and nutrient run-off. Water harvested for stock and domestic use from farm dams, waterways and groundwater bores outside of the allocation and licensing framework can also have a significant impact on flows into waterways and wetlands.

Integrating the management of the surrounding catchment with waterway management is critical and success relies on participation of the region’s public and private landholders. This is particularly important in the Corangamite region’s highly modified catchments, where 78% of the catchment is in private ownership and a large proportion used for agriculture.