Welcome to Country

The following statement (in Maar language and in English) is from the Eastern Maar— ‘watnanda koong meerreeng, tyama-ngan malayeetoo’

Ngatanwarr

Ngeerang meerreeng-an

Peepay meerreeng-an

Kakayee meerreeng-an

Wartee meerreeng-an

Maara-wanoong, laka. Wanga-kee-ngeeye

Meereeng-ngeeye, pareeyt, nganpeeyan, weeyn, wooroot, poondeeya-teeyt

Meerreeng-ngeeye, nhakateeyt, woorroong, leehnan, mooroop, keerray

Meerreeng-ngeeye, thookay-ngeeye, pareeyt pareeyt ba waran waran-ngeeye, wangeeyarr ba wangeet – ngeeye, maar ba thanampool-ngeeye, Ngalam Meen-ngeeye, mooroop-ngeeye

Meerreeng-ngeeye Maar, Maar meerreeng

Wamba-wanoong yaapteeyt-oo, leerpeeneeyt-ngeeye, kooweekoowee-ngeeye nhakapooreepooree-ngeeye, keeyan-ngeeye Wamba-wanoong nhoonpee yaapteeyt-oo, tyama-takoort meerreeng

Peetyawan weeyn Meerreeng, nhaka Meerreeng, keeyan Meerreeng, nganto-pay ngootyoonayt meerreeng

Kooweeya-wanoong takoort meerreeng-ee ba watanoo Meerreng-ngeeye, yana-thalap-ee ba wanga-kee Meerreeng laka

Ngeetoong keeyan-ngeen Meerreeng, Meerreeng keeyan ngooteen

Together body and Country, we know long time.

(We see all of you), greeting.

Mother my Country.

Father my Country.

Sister my Country.

Brother my Country.

We are the Maar speaking Peoples. Hear us.

Our Country is water, air, fire, trees, life.

Our Country is thought, language, heart, soul, blood.

Our Country is our Children, our youth, our Elders, our men and women, our Ancestors, our spirit.

Our Country is Maar, Maar is Country.

We bring to the light our songs, our stories, our vision, our love.

We bring these things to the light so All can know Country.

To care for Country. To think about Country. To love Country. To protect Country.

We invite all that choose to live on or visit our Country to slow down. To tread softly and listen to Country speak.

If you love Country, Country will love you.

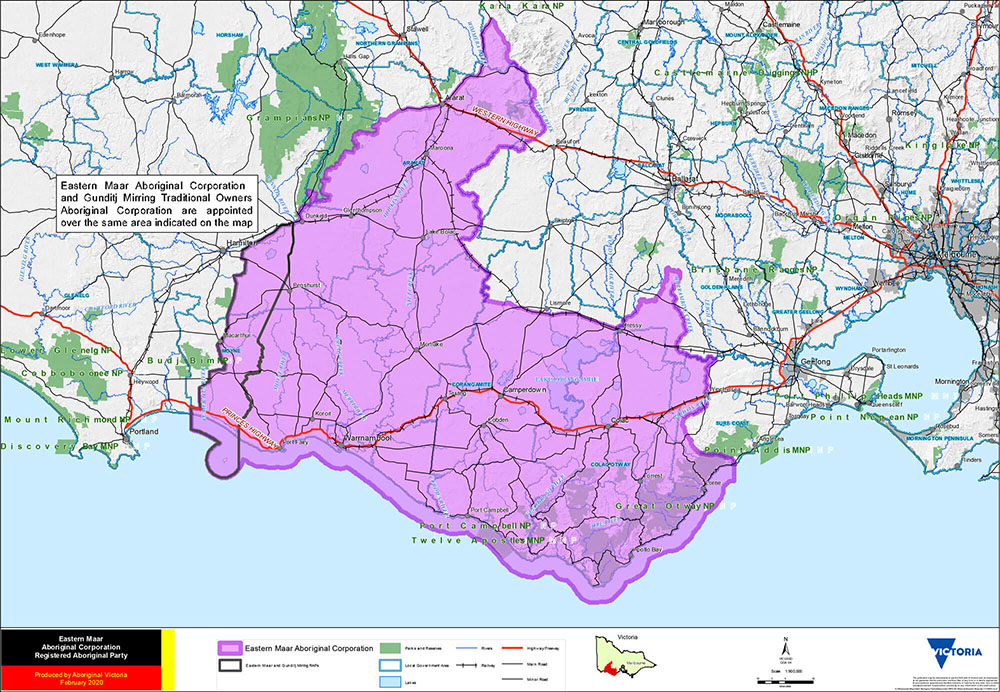

The Eastern Maar are Traditional Owners in south-western Victoria. Our land extends as far north as Ararat and encompasses the Warrnambool, Port Fairy and Great Ocean Road areas. It also stretches 100m out to sea from low tide (see map 1 below).

Eastern Maar is a name adopted by the people who identify as Maar, Eastern Gunditjmara, Tjap Wurrung, Peek Whurrong, Kirrae Whurrung, Kuurn Kopan Noot and/or Yarro waetch (Tooram Tribe) amongst others, who are Aboriginal people and who are:

- descendants, including by adoption, of the identified ancestors

- who are members of families who have an association with the former Framlingham Aboriginal Mission Station

- who are recognised by other members of the Eastern Maar People as members of the group.

Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation (EMAC) is the professional organisation that represents the Eastern Maar People of South West Victoria and manages their Native Title rights and interests. EMAC has a board of directors of Traditional Owners and is a registered organisation under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006. (EMAC Website)

EMAC is governed by a 12 member Board – each member represents a defined family grouping which is linked to a referenced ancestor who occupied territory at the time of European settlement. Up to 60% of its 12-member board is represented by proud Eastern Maar women, some of whom are senior Elders and applicants to EMAC’s Native Title claim. EMAC operates as a society that has a unique decision-making structure – one which is committed to collectivism and inclusion, and which values common goals over individual pursuits.

The contemporary Eastern Maar nation traces an unbroken line of descent back to our ancestors over many thousands of years. We have survived as our Country’s First People and, despite the well documented colonial history, continue to maintain economic, traditional, cultural, familial and spiritual ties to our homeland. Through the leadership and authority of our Elders, we are practising our laws and customs, strengthening our system of governance and nurturing our connection to Country.

We continue to pass on our traditional knowledge from generation to generation, inducting our young people into Maar society as a cultural practice initiated by our Ancestors. It is a process that keeps customs and stories alive and ensures we are able to maintain Maar culture, language and society. Drawing strength from our identity and past, we are able to live our culture as a set of attitudes, customs, and beliefs; helping us to be resilient and adaptable in changing circumstances.

We are the eastern landholding group of a larger Aboriginal nation – the Maar Nation. The western landholding group of this Maar nation are the Gunditjmara, with whom we share the lands and waters between the Eumeralla and Shaw Rivers. The Country to the east of the Shaw River to the Leigh and the Barwon catchment basins, and the area from the sea in the south to the Great Dividing Range in the north belongs to Eastern Maar.

Before the arrival of Europeans, with their diseases and ambition to take over our Country, there were over 200 clan groups belonging to the Maar nation. This number diminished quickly to just a fraction of the original population, with small groups coalescing into larger ones, and yet larger ones still until there were only two Maar landholding groups left, each covering a large area of land and water.

In accordance with our law and custom, clans that became incapacitated were superseded by others who remained strong, handing on their sanctioned place in the landscape and responsibilities for looking after the clan estate. This process ensured that the cultural values and practices of Maar citizens remained intact.

Today some of our citizens continue to identify with the respective Maar clan groups of their ancestors, including Peek Whurrong, Chap Whurrong (Tjap Wurrung or Djab Wurrung), Kirrae Whurrong, Kuurn Kopan Noot and Yarro Waetch (Tooram Tribe). Other citizens comfortably identify as part of the broader Eastern Maar group without identifying with a particular clan. (From Eastern Maar Country Plan: Meerreengeeye ngakeepoorryeey, p6.)

The Creation story of Warrion, the bandicoot, is centered around Mount Warrion and its lava flow. The story tells of how Warrion’s ancestor, a megafauna predecessor of the modern-day bandicoot, created the many small water holes East and South of Warrion hill by using his tail as a club. Warrion did this in order to change the direction of water flow away from Koorrang Koorrang, a saline lake to the west of Mount Warrion, toward Lake Colac. Koorrang Koorrang (Lake Corangamite), is Koorrang Meerreeng (Snake Country), and if too much water flows into the lake the sleeping woman will wake, flooding all the surrounding lands with her tears.

The story above is an example of a rich Maar cultural mosaic landscape that is now part of south west Victoria. Pang-ngooteekeeya weeng malangeepa ngeeye is a project that will examine and reintroduce the cultural land and water management practices of the Maar nation. It will use the creation stories such as the one above to inform EMAC of the management objectives of each Country and how to implement them. (“Pang-ngooteekeeya weeng malangeepa ngeeye, Remembering our Future – Bringing old ideas to the new” project plan; 2020)

Meerreengeyye ngakeepoorryeeyt (Country Plan)

For Aboriginal people, Country is more than the land, water and air, the plants and animals. It’s more than just what we can see – it’s our spirituality, our Ancestors and our connection. It is the way we feel, the way we live and the connection that holds and defines us. When the health of our Country declines, so does the health of our citizens – we are all inextricably linked.

We have had responsibility for caring for our Country for thousands of years. We have never simply taken from our Country without understanding the natural systems and managing them so that they stay healthy and keep providing for us. But that responsibility has been taken away. Much of our land is now farmland that we are not allowed to access, and the natural resources have been degraded. Rivers have been diverted creating saline lakes that no longer support the wildlife that was once there. The extensive land clearing has removed habitat for many of the animals that we relied on. Even sites with international obligations are not being managed properly and we are worried that our Country cannot take much more.

Through Meerreengeyye ngakeepoorryeeyt – our Country Plan – we have defined our vision for the future. To help us on the path to achieving our vision, we have identified six goals that will form the focus of our efforts. For each of our goals, we have a number of objectives that we will work towards – as individuals, as a nation and in partnership with others. These goals are underpinned by the law of the land, our oral authority that dictates how we live and behave, who we interact with and how we will always care for our Country.

Major threats and drivers of change

Climate Change, rising sea levels, coastal erosion, dune erosion.

Threats to Cultural Heritage. Strategically select sites to protect. EMAC conduct their own excavations and research at sites at risk. Direct learning opportunity – history plus techniques.

“Biggest threat to our Country is whitefellas. Not the people but the culture.”

Lack of capacity is EMAC’s biggest current challenge.

Desired outcomes for the future

One of the biggest challenges to collaborative land management is the way different parts of society define conservation. We see ourselves as part of the landscape and our philosophy is based fundamentally on sustainable use, which can include resource extraction and utilisation under the right circumstances. We need others to understand and respect this if we are to work together to ensure Country becomes healthy and productive into the future.

The RCS should lay the ground for change, plant the seed for changes that are coming. Articulate that change through the whole document, not just one part.

Community

20 year desired outcome:

By 2042, Integrated catchment management supports Traditional Owner self-determination

6 year outcomes:

EMAC1 By 2027, Traditional Owners rights, interests, obligations and access to Country and water, including cultural flows, are acknowledged and protected.

EMAC2 By 2027, Traditional Owner groups are decision makers and provide strategic leadership in Integrated Catchment Management.

EMAC3 By 2027, the social wellbeing of Traditional Owner communities increases as a result of involvement in Integrated Catchment Management.

EMAC4 By 2027, the economic benefit for Traditional Owner communities increases as a result of involvement in Integrated Catchment Management.

EMAC5 By 2027, there is an increased connection between agencies, authorities and community groups and Traditional Owner communities to raise awareness and understanding of cultural landscapes management.

Water

20 year desired outcome:

Rivers:

By 2042, Traditional Owner communities are decision makers and provide strategic leadership for river Country.

Wetlands:

By 2042, the function and resilience of wetlands is maintained or improved.

6 year outcomes:

Rivers:

EMAC6 By 2027, Traditional Owners rights, interests, obligations and access to water, including cultural flows, are acknowledged and protected.

EMAC7 By 2027, Traditional Owner communities have the capacity, knowledge and authority to look after river Country including cultural flows.

Wetlands:

EMAC8 By 2027, Traditional Owner communities have the capacity, knowledge and authority to look after wetlands and their restoration including cultural flows.

Coast and Marine

20 year desired outcome:

Traditional Owner communities are decision makers and provide strategic leadership for sea Country.

6 year outcomes:

EMAC9 By 2027, Traditional Owners rights, interests, obligations and access to the marine and coast environment, including water and cultural flows, are acknowledged and protected.

EMAC10 By 2027, Traditional Owner communities have the capacity, knowledge and authority to look after sea Country.

EMAC11 By 2027, there is increased understanding and protection of at risk Aboriginal cultural values and heritage sites along the coastline.

Biodiversity

20 year desired outcomes:

Native Vegetation:

By 2042, the condition, function and resilience of native ecosystems will be maintained or improved.

Threatened Species:

By 2042, the health of key populations of threatened species and communities is maintained or improved.

6 year outcomes

Native Vegetation:

EMAC12 By 2027, Traditional Owner communities have the capacity, knowledge and authority to look after their understanding of native habitats, including culturally significant species, and groundwater dependent systems.

Threatened Species:

EMAC13 By 2027, Traditional Owner communities have the capacity, knowledge and authority to look after their understanding of threatened native species, including culturally significant species, and groundwater dependent species and communities.

Land

Land Use

20 year desired outcome:

By 2042, land managers are supported to manage land and water within its capability

6 year outcome:

EMAC14 By 2027, there is increased understanding and protection of Aboriginal cultural values and heritage across the landscape and throughout the communities.

Sustainable Primary Production

20 year desired outcome:

By 2042, there is an increase in the capacity of land managers and agriculture systems to adapt to significant changes in climate and market demands.

6 year outcome

EMAC15 By 2027, Traditional Owners lead the regional development of the native food and botanical industry.