Overview

| Overall area | 233,373 hectares |

| Population | 20,946 |

| Climate | 502 mm per annum at Lal Lal |

| Main towns | Bunninyong Meredith Smythesdale Linton Gordon Dunnstown |

| Land use | Broadacre grazing Cropping Horticulture Viticulture Poultry Plantation forestry |

| Main Industries | Agriculture Nature based-tourism Urban water supply Forestry |

| Main Natural Features | Moorabool River Leigh River Yarrowee River Leigh River Gorge Mount Buninyong Mount Mercer Mount Warrenheip Enfield State Park Steiglitz Historical Park Lal Lal Falls |

Landscape

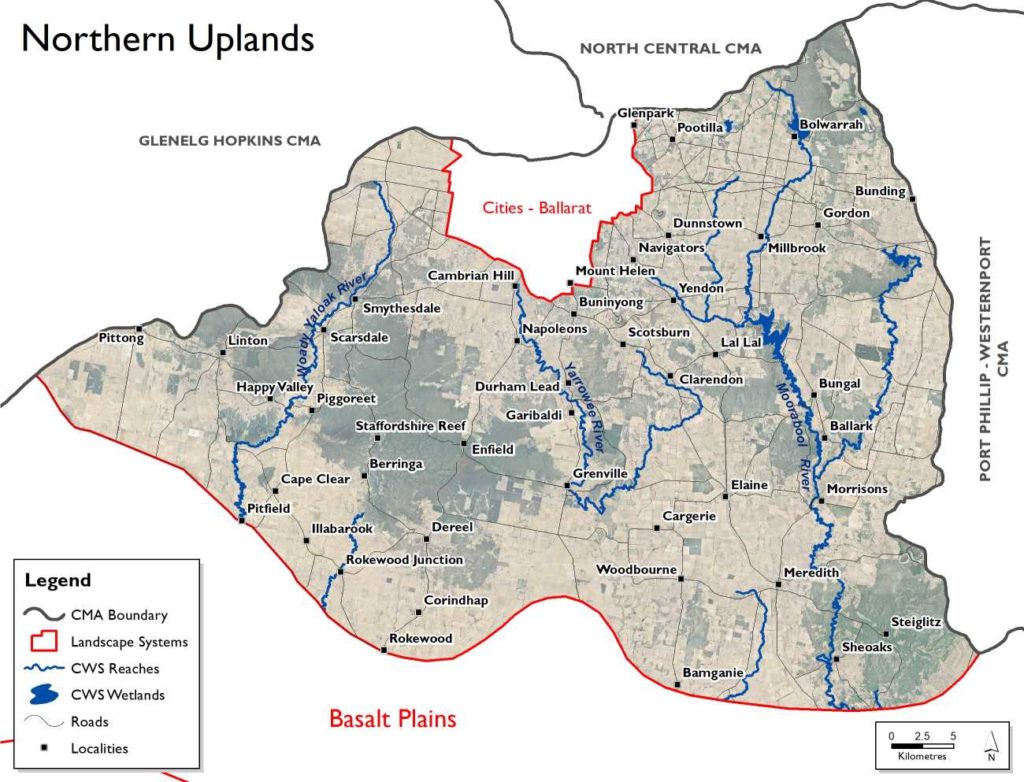

This area spans the northern part of the region and extends from Ballarat in the north, is bounded in the south by the Basalt Plain and includes the townships of Meredith, Rokewood and Skipton, but does not include the urban area of Ballarat City which forms its own landscape system. Undulating hills and broad valleys characterise the landscapes formed on folded sedimentary rocks and granite plutons formed around 450 to 350 million years ago. Remnants of an ancient plain, formed about 40 to 30 million years ago, occur as caps of gravels sporadically distributed at various elevations. The majority of this landscape system is within the Central Victorian Uplands Bioregion.

Of particular local significance for their environmental values are the gorges extending along parts of the Leigh River. Due to the gorge’s steep escarpments they remain largely non-arable, protecting bands of remnant vegetation and providing important corridors of habitat for wildlife.

The Northern Uplands is split vertically across three catchment basins – Lake Corangamite, Barwon River and Moorabool River Basins. Three river systems drain the Northern Uplands of the Corangamite Region – the Moorabool River (east), Leigh River (central) and Woady Yaloak River (west). The Northern Uplands system is also the home to a number of other priority waterways including Lal Lal Creek, Spring Creek, Yarrowee River, Williams Creek and Little Woady Yallock Creek (upper).

Other environmental values identified include:

- known rare and threatened species

- significant Ecological Vegetation Classes

- rural water source

- aquatic invertebrate communities.

Livelihood

Most of the land in this landscape system is privately owned (approximately 80%).

The area contains highly productive agricultural and horticultural areas used for broadacre grazing and cropping, with some areas of intensive agriculture, including horticulture, viticulture and poultry. There are also large areas of pine plantations.

Lifestyle

The Northern Uplands supports a population of over 27,500 – around 6.7% of the Corangamite region. The most densely populated areas of the Northern Uplands are around the townships of Gordon, Mount Helen and Buninyong. The municipalities of the Ballarat, Golden Plains and Moorabool are partly covered in the system. The Traditional Owners are the Wadawurrung.

This landscape system has a rich gold mining history. The gold rush period of the mid to late 1800s, while notable in the colonial history of Victoria, also had a major impact on the health of the Yarrowee, Leigh and Moorabool rivers. The Moorabool River, its associated tributaries and water storages in the north form part a ‘Special Water Supply Catchment’ and are a source for urban and rural township water including Ballarat, Geelong and Meredith.

The area’s goldmining and cultural heritage and diverse landscapes attract many visitors and residents. The natural resources in the area support industries such as agriculture and nature based-tourism, supply urban water needs and provide important habitat for flora and fauna. Major features include Mount Buninyong, Mount Mercer and Mount Warrenheip along with the Enfield State Park and Steiglitz Historical Park.

The natural resource community of the Northern Uplands Landscape System is very robust with a good coverage through groups. Many of these groups come under the umbrellas of the Leigh Catchment Group and Moorabool Landcare Network. The Bunanyung Landscape Alliance is an alliance of community members, Landcare and Friends groups, networks and associations involved in promoting the health of biodiversity for the urban and rural catchments of the Moorabool, Leigh and Woady Yaloak waterways.

There is a diverse array of community groups engaged in natural resource management or environmental volunteer or lobbying activities. Community based groups in this area include the Ross Creek Landcare Group, NapoleonsEnfield Landcare Group, Garibaldi Landcare Group, Meredith Bamganie Landcare Group, Upper Williamson’s Creek Landcare Group, Moorabool Catchment Landcare Group, East Moorabool Landcare Group, Lal Lal Catchment Landcare Group and Wattle Flat/Pootilla Landcare Group. Many of these groups come under the umbrellas of the Leigh Catchment Group and Moorabool Landcare Network.

Assessment of current condition and trends

Water

Major waterways of the Northern Uplands include the Woady Yaloak River, Little Woady Yallock Creek, Yarrowee River, Moorabool River and its tributaries.

The Northern Uplands is split vertically across three catchment basins – Lake Corangamite, Barwon River and Moorabool River Basins. Assessed through the Victorian Index of Stream Condition (ISC) in 2010, the overall condition of the Northern Uplands waterways was mixed, ranging from very poor to moderate, with over half found in moderate condition. One exception was the reach of the Little Woady Yallock Creek, which is rated excellent – the only site outside the Otway Basin in the entire Corangamite region. The four waterway reaches closest to the Ballarat urban area all rated very poorly.

The Moorabool River is considered one of the most flow-stressed rivers in the state. This system is the home of the region’s first flagship waterway ‘The Living Moorabool’ (Program site – downstream of Lal Lal Reservoir to the confluence of the Barwon River, including Sutherlands Creek). The Moorabool River has an Environmental Water Entitlement that is held in Lal Lal Reservoir; however this entitlement is not enough to sustain the natural assets of the river. The increase of farm dams within the system is one of the causes of decreased volumes of water entering the priority waterways.

The gorges and steep escarpments of the Moorabool and Leigh Rivers remain largely non-arable, protecting bands of remnant vegetation and providing important corridors of habitat for wildlife. However, many reaches within this system still require riparian fencing, establishment of native indigenous vegetation and woody weed control (willows, gorse, blackberry) as well as terrestrial pest animal control.

Weirs and bridges placed in the Moorabool and Leigh rivers to support agriculture activities over the last century have created fish barriers within the rivers which cause issues for fish migration, and even fish deaths, when the rivers cease to flow.

Of waterways tested from the Lake Corangamite Basin, the Little Woady Yallock Creek notably displayed near natural condition regarding hydrology.

For the Barwon River Basin waterways of the Northern Uplands, flow regimes varied. One reach of the Yarrowee River near Ballarat was among the poorest scoring in the basin. Most of the reaches from the Barwon River Basin (all tributaries of the Leigh River) exhibited extended periods of both low and zero flow in summer. Two of these reaches, one from the Yarrrowee River and the other from Winter Creek, also displayed low flows during winter, attributed to diversions, rainfall patterns and catchment modifications.

Of waterway reaches tested from the Moorabool River Basin, flow regimes were among the most highly modified of the entire Corangamite region. The two waterway reaches tested closest to the Ballarat urban area, Spring Creek and Lal Lal Creek, notably had extremely modified flow regimes, with periods of zero flow in summer, and extended periods of low flow in both summer and winter.

Corangamite Waterwatch, a citizen science volunteer program, regularly monitors water quality parameters at many sites across the catchment; however, Waterwatch data for the Yarrowee-Leigh River is limited. Both monitoring sites are in the upper catchment, one upstream and one downstream of Ballarat. The water quality at the upstream site was mostly healthy, though at times displayed low dissolved oxygen and high turbidity. The site lacks native riparian vegetation and instream cover for aquatic organisms. The macroinvertebrate community indicate the site to be mildly to heavily impacted. The water quality of the downstream site was mostly healthy however phosphorus levels were high. High levels can stimulate excessive aquatic plant and algal growth which may impact on the beneficial uses. The riparian vegetation and aquatic habitat are degraded at this site and the macroinvertebrate community suggest the site is mildly impacted.

Williamsons Creek, a tributary of the Yarrowee-Leigh River, displayed relatively poor water quality. This intermittent stream exceeded most of the SEPP (Waters) water quality objectives. High electrical conductivity levels at times indicate the ingression of saline groundwater at times of low or no flow. The macroinvertebrate community indicate the site to be mildly to heavily impacted; in times of increased river flow (low electrical conductivity) more sensitive macroinvertebrate communities are present.

The water quality in the Moorabool River has changed over time. Before 2011, high salinity was common, due to water extraction and reduced flows associated with the Millennium drought. Post 2011, the introduction of environmental flows, particularly over summer to autumn, helped lower salinity and improve dissolved oxygen levels. Salinity levels were high in the East Branch in comparison to the West Branch, whilst reactive phosphate levels were higher in the West Branch. At the confluence of the East and West Branch the water quality is maintained at relatively healthy levels. Increases in salinity occur downstream, likely influenced by seasonal flow from the tributaries such as Teatree and Sutherland Creeks. There is evidence that during low flow, saline groundwater enters these streams. Whilst the sites on these waterways have good riparian vegetation and aquatic habitat, the macroinvertebrate community structure indicates the water quality to be degraded.

Throughout the Moorabool catchment the habitat quality is degraded. A lack of riparian vegetation, unrestricted stock access and poor aquatic habitat are evident. The implementation of environmental flows has improved the overall water quality in the Moorabool River, particularly the East Branch, whilst over time it appears dissolved oxygen levels have marginally declined .

Biodiversity

The Moorabool River Environmental Entitlement allows an average of 2,500 ML (depending on climatic conditions) to be delivered downstream of Lal Lal Reservoir. Where possible it is used to improve flows downstream of She Oaks Weir to the Barwon River. The entitlement helps to preserve native fish, including non-migratory species such as River blackfish, Australian smelt and southern pygmy perch, as well as short-finned eel and tupong. Other ecological values in the reach include a diverse population of macroinvertebrates, and widespread platypus and water rat populations.

The Moorabool River reach between Lal Lal Reservoir and She Oaks contains some of the most valuable in-stream and riparian habitats in the catchment, with remnant populations of threatened Ecological Vegetation Communities (EVCs) such as Stream Bank Shrub land and Riparian Woodland. Diverse macroinvertebrate communities and several non-migratory native fish species were recorded, in addition to migratory Buniya (Short-finned eels). The river reach from the Moorabool River East Branch (near Morrisons) to She Oaks Weir passes through extensive tracts of remnant native vegetation, including State and National Park between Morrisons and Meredith. Native fish recorded include non-migratory species such as River blackfish, Australian smelt and Flat-headed gudgeon (Tunbridge, 1988). Other ecological values in the reach include a diverse population of macroinvertebrates, platypus and rakali (Williams & Serena, 2006).

For the Barwon River Basin waterways of the Northern Uplands, most sites have vegetation in poor or moderate condition. For waterway reaches of the Moorabool River Basin, streamside vegetation quality varies, with most reaches being bereft of large trees. Sutherland Creek West Branch has vegetation in near-reference condition, the best of the catchment basin. Spring Creek’s reach, near Ballarat, is among the poorest quality for the basin regarding vegetation, with low levels of diversity, vegetation width and continuity. For waterways from the Lake Corangamite Basin, streamside vegetation quality is generally poor. Kuruc-a-ruc Creek and Little Woady Yallock Creek represent the Lake Corangamite Basin’s only excellent streamside vegetation, with near-reference condition.

DELWP’s Habitat Distribution Models identify species with more than 5% of their Victorian range in this area, include notable plant species such as Golden Bushpea (rare, 56%), Brisbane Ranges Grevillea (rare, 47%), Gum-barked Bundy (vulnerable, 39%), Brittle Greenhood (endangered, 29%), Enfield Grevillea (vulnerable, 82%), Wombat Bush-pea (rare, 12%), Golden Bush-pea (8%), Yarra Gum (rare, 7%), Australian Sheep’s Burr (6%), Bicolour Everlasting (6%), White Sunray (endangered, 34%), Turf Curly Sedge (rare, 30%), Salt-lake Tussock-grass (vulnerable, 25%), Clumping Leek-orchid (endangered, 24%), Grassland Sunorchid (endangered, 24%), Button Wrinklewort (endangered, 24%), Basalt Sun-orchid (endangered, 24%), Fragrant Leek-orchid (endangered, 23%), Spiny Peppercress (endangered, 21%).

According to DELWP’s Habitat Distribution Models, the following reptiles have more than 5% of their Victorian range in the area: the Grassland Earless Dragon (critically endangered, 10%), Tussock Skink (vulnerable, 10%), Southern Grass Skink (least concern, 8%), Striped Legless Lizard (endangered, 7%), Corangamite Water Skink (critically endangered, 5%). The only bird to have 5% of their Victorian range in the area is the Brolga (vulnerable, 6%).

The following Ecological Vegetation Classes in the region are classified as endangered: Grassy Woodland, Plains Grassy Woodland, Damp Sands Herb-rich Woodland, Wetland Formation, Plains Sedgy Wetland, Sand Forest, Stream Bank Shrubland, Escarpment Shrubland, Alluvial Terraces Herb-rich Woodland, Swampy Riparian Woodland, Creekline Grassy Woodland, Plains Grassy Wetland, Riparian Woodland, Aquatic Herbland/Plains Sedgy Wetland Mosaic, Plains Grassland, Floodplain Riparian Woodland, Creekline Herb-rich Woodland, Grassy Woodland/Heathy Dry Forest Complex, Brackish Drainage-line Aggregate.

Land

Land clearing for farming, timber and fuel production, gold mining and other land uses in the late 1800s and early 1900s brought rapid reduction in the quantity and quality of vegetative cover in this landscape. During this period, hoofed animals were introduced and wetlands were drained for agricultural purposes. A significant change in the condition of soil and water resources was caused by these activities.

Relative soil productivity on private agricultural land in the Northern Uplands is highly variable, ranging inconsistently between low to high across the whole area. The area of lowest productivity is concentrated in the southeast corner, below the Brisbane Ranges National Park.

Taken from DELWP’s Victorian Land Cover Time Series, the most common land cover classes in the Northern Uplands are non-native pasture, followed by native trees, native grass herb, pine plantation and dryland cropping. Over a 30-year period, non-native pasture decreased, from 58% to 51% of the total landscape system. Native tree coverage increased from 25% to 27%, and native grass herb increased from 4.5% to over 5% of the total area.

Dryland cropping has increased ten-fold since 1985, now occupying over 3% of the total Northern Uplands. Exotic woody vegetation has more than doubled to cover 1.3% of the total landscape system, and hardwood plantations experienced a six-fold increase, now covering 2% of total land area. Although still a tiny proportion of the landscape system (<1%), urban areas more than doubled. Native scattered trees and both seasonal and perennial wetlands all experienced small decreases. Irrigated horticulture has more than halved, now occupying under 1% of the total area.

Community

The Northern Uplands supports a population of over 27,500 – around 6.7% of the Corangamite region. The most densely populated areas of the Northern Uplands are around the townships of Gordon, Mount Helen and Buninyong.

Community based groups in this area include the Ross Creek Landcare Group, NapoleonsEnfield Landcare Group, Garibaldi Landcare Group, Meredith Bamganie Landcare Group, Upper Williamson’s Creek Landcare Group, Moorabool Catchment Landcare Group, East Moorabool Landcare Group, Lal Lal Catchment Landcare Group and Wattle Flat/Pootilla Landcare Group. Many of these groups come under the umbrellas of the Leigh Catchment Group and Moorabool Landcare Network.

Other environmental groups:

- Back to Steiglitz Association

- Friends of Clarkesdale Bird Sanctuary

- Friends of the Union Jack Reserve

- Mount Buninyong Management Advisory Committee

Major threats and drivers of change

Most major threats are natural processes, albeit some are the consequences of land clearing, agricultural, forestry and urban development. The consequences of these threats impacting on land and agriculture have also become greater. For instance, built infrastructure has spread across wider areas with a larger proportion of the population served by various utilities, roads etc. A growing and expanding human population requires larger volumes of water. High value biodiversity, wetlands and cultural heritage sites are considered more significant and valuable as their number has declined.

Water

Much of the Leigh, Moorabool and Woady Yaloak rivers and their associated tributaries have been subjected to grazing pressures. Livestock access to waterways can erode banks, damage riparian vegetation and reduce water quality through sedimentation and effluent contamination. Within river channels there are a number of threats to the condition of the waterway, which include bed instability and degradation, change in flow regime and reduced riparian connectivity, degraded riparian vegetation and reduced vegetation width, and loss of instream woody habitat.

Within this area, increasing salinity, nutrients and turbidity are the dominant threats to the health of the waterways and water bodies.

The Corangamite Waterway Strategy 2014-2022 outlines priority management activities to address water quality threats in the Yarrowee-Leigh and Moorabool landscapes. These include:

- Establish terrestrial pest animal control – rabbit control

- Establish native indigenous vegetation

- Install riparian fencing

- Establish stewardship/management agreement

- Undertake woody weed control

- Implement best management practice on grazing properties

- Undertake assessment and management of fish barriers in the Barwon and Moorabool catchments (Moorabool River)

- Maintain the discharge into the Yarrowee Leigh from South Ballarat Treatment Plant as a beneficial environmental use, as per the Central Region Sustainable Water Strategy, and examine opportunities to better replicate natural flow regimes (Leigh River, Yarrowee River)

- Adopt whole of water cycle management principles to reduce the impact of stormwater run-off on the health of Yarrowee Leigh and downstream waterways (Yarrowee River)

- Enhance the upstream reach in line with the Breathing Life back into the Yarrowee Project (Yarrowee River)

- Deliver current environmental water entitlement and develop long-term planning for environmental watering of the Moorabool River (EWMP) (Moorabool River, Moorabool River West Branch)

- Investigate impacts to environmental flows throughout the broader Moorabool catchment basin to secure and better manage environmental water where required (Moorabool River, East and West branches)

- Undertake an assessment of instream habitat (large wood) density (Moorabool River)

- Comply with bulk entitlements, monitor and maintain waterway condition and implement risk management plans as appropriate (Lal Lal Reservoir, Wilsons Reservoir, Moorabool Reservoir, Bostock Reservoir, Korweinguboora Reservoir)

- Develop land and gully stabilisation plan for the Eclipse Creek catchment (Moorabool River)

- Maintain Waterwatch groups collecting baseline data on waterway condition.

Biodiversity

Threats identified are illegal tracks, littering, barriers to on-ground management, inappropriate land use, water quality and quantity, native vegetation removal, urban encroachment, wildfire, Phytophthora cinnamomi.

Gorse (Ulex europaeus) and serrated tussock (Nassella trichotoma) are significant weeds and are known to adversely impact biodiversity, productivity and recreation. The European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) is also a threat in this landscape system. Willows (Salix spp.) are a Weed of National Significance and are known to adversely impact waterways through reducing water quality and availability, increasing erosion and flooding potential, and reducing aquatic and riparian biodiversity. The red fox (Vulpes vulpes) was identified as a threat to significant bird species.

In the East and West branches of the upper Moorabool, highly regulated hydrology, with associated alteration of geomorphology, may have detrimentally impacted river function and ecology. Farm dams and irrigation diversions can also have a detrimental impact through alterations of flow regime and water quality. Lack of adequate flows or changes to the flow regime – including the timing, magnitude or frequency of flows at different times of the year – can pose a risk to biodiversity. Without provision of critical dry period low flows, there wouldn’t be sufficiently deep pools of water to ensure survival of many aquatic species. Low flows during the drier months also provide minimum water velocity for mixing of pools, reducing the risk of stratification and poor water quality. Freshes, or small “pulses” of water, delivered in the wet period are critical to create spawning opportunities for fish and other fauna. Without adequate freshes, populations of species would reduce. An extended dry conditions flow regime is likely to result in localised extinctions of a number of these species, with severely reduced opportunities for spawning and reproduction for resident and migratory fish, Growling grass frog and macroinvertebrates.

Water quality parameters for these reaches were often outside of State Environment Protection Policy (SEPP) objectives. A knowledge gap exists for the current biological condition of the East Moorabool. Threats to native fish include exotic species such as Brown trout and Redfin.

DELWP’s 2019/2020 Biodiversity Response Planning identifies the most cost-effective threat control actions for significant biodiversity improvement in the region. The most beneficial actions in this region are control of goats, pigs, rabbits and weeds, and permanent protection.

Land

Gully/tunnel erosion, sheet/rill erosion, wind erosion, landslides, soil structure decline, acid sulphate soils, secondary salinity and waterlogging present the major threats to soils and land use within this landscape (see Static Maps section for mapped soil threats).

Sheet and rill erosion threaten agricultural productivity through the removal of fertile topsoil. Once removed, this topsoil is often deposited in waterways, threatening water quality through sedimentation and nutrient inputs. Tunnel erosion impacts on agricultural land, water quality and infrastructure associated with residential development. Gully erosion is the ultimate result of both tunnel and rill erosion. Gullies are the most visually obvious representation of erosion in the landscape. In many areas, gully erosion is a legacy of past land use, particularly gold mining along creeks.

Acid sulphate soils naturally occur in the Corangamite Region. These soils have sediments containing iron sulphides below the soil surface. When these naturally occurring sulphides are disturbed and exposed to air, oxidation occurs and sulphuric acid is produced.

Waterlogging may be a natural condition of the soil, but can worsen with deterioration in soil structure. There is a strong relationship between high likelihood of soil structure deterioration and a high susceptibility to waterlogging. These susceptible areas are generally located on low-lying heavy duplex soils in higher rainfall areas and can lead to restricted root growth, reduced infiltration rates, increased likelihood of surface run-off, water erosion and surface ponding.

Community

The community of the Northern Uplands Landscape System is very robust with a good coverage through groups including Ross Creek Landcare Group, Napoleons Enfield Landcare Group, Garibaldi Landcare Group, Meredith Bamganie Landcare Group, Upper Williamson’s Creek Landcare Group, Moorabool Catchment Landcare Group, East Moorabool Landcare Group, Lal Lal Catchment Landcare Group and Wattle Flat/Pootilla Landcare Group. Many of these groups come under the umbrellas of the Leigh Catchment Group and Moorabool Landcare Network.

Major threats to the community in this Landscape System are the expansion of the City of Ballarat and the change in land management. The changing demographic of the farming sector with the average age of full time farmers becoming older is of concern, with fewer younger people taking over the operation of farms. Farms changing their principal business is also an issue with wind farming and soft wood plantations becoming more prevalent.

The absorption and/or corporatisation of properties into conglomerates is also a threat to the communities within this landscape. Many of the smaller towns such as Meredith, Gordon, Scarsdale and Linton rely heavily on the agriculture sector.

Northern Uplands 6 Year Outcomes

Water

By 2027, compared to 2022 baselines:

The efficiency of consumptive water use in the Northern Uplands Landscape System will be improved through the use of cost effective alternate water sources and demand management strategies that results in less take from source water. NorWO1

There is an improvement in riparian extent and condition of hydrological regimes and water quality in priority reaches defined in the Corangamite Waterway Strategy. NorWO2

Drinking water supply catchments are managed to provide quality water for urban water supplies. NorWO3

Improve waterway amenity through the implementation of the Kitjarra-dja- bul bullarto langi-ut Masterplan in the Northern Uplands Landscape System. NorWO4

Increase the community understanding and awareness of water values and management. NorWO5

Water quality values are defined and managed for. NorWO6

Ensure Wadawurrung people have a strong voice in the management of the Moorabool, Yarrowee and Leigh rivers and cultural values are incorporated. NorWO7

Biodiversity

By 2027, compared to 2022 baselines:

Achieve a net gain in the overall extent, connectivity and condition of Northern Uplands habitats across land and waterway environments through effective climate change adaptation strategies. NorBO1

Achieve a net gain where possible in suitable Northern Uplands habitat expected over 6 years from sustained improved public and private land management and community involvement for threatened and culturally significant local species. NorBO2

Achieve a net gain where possible in all species with positive % change in suitable Northern Uplands habitat and improved species balance expected over 6 years from sustained improved public and private land management and community involvement including pest plant and animal control. NorBO3

Increase effectiveness of interagency collaboration in their ability to respond to climate change and development pressures on biodiversity. NorBO4

Increase understanding and awareness of biodiversity values of the Northern Uplands Landscape System. NorBO5

Land

By 2027, compared to 2022 baselines land within the Northern Uplands is sustainably managed for a variety of purposes within its capability and suitability to maintain and improve its natural capital and to prevent both on and off-site impacts. NorLO1

Communities

By 2027, compared to 2022 baselines:

Northern Uplands communities (and visitors) are encouraged, educated and enabled to further connect with and responsibly care for the natural environment. NorCO1

Northern Uplands communities (and visitors) have an increased awareness and understanding of the connection between human activities and impacts on the environment. NorCO2

The increased capacity of the Eastern Maar and Wadawurrung Traditional Owner Groups enables their increased involvement in decision making that effects their Country. NorCO3

Northern Uplands 6 Year Priority Directions

Six year regionally applicable priority directions have been developed for each of the Themes and are applicable to this landscape System, these can be accessed via the following links:

Six year priority directions for the Northern Uplands are provided in the following table. Where these priority directions apply to a theme this is indicated by the relevant shading. To access definitions of terms and acronyms click on the following link.

Code |

Priority Direction |

Relevant Theme | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Biodiversity | Land | Community | Lead | Collaborators | |||

| NOR1 | Northern Uplands landscape partners and the community collaborate to deliver a coordinated approach to natural resource management to build resilience and successfully respond to changing circumstances with clear roles and responsibilities communicated. | CCMA | DELWP, BW, CHW, EPA, BCC, GPS, MSC, PV. | |||||

| NOR2 | Develop enduring partnerships with the Wadawurrung people to: 1) acknowledge and enhance Wadawurrung values of natural assets; 2) ensure the Wadawurrung people have a strong say in management of natural assets; 3) identify and implement appropriate mechanisms for sharing Wadawurrung stories and history; and, 4) identify and implement opportunities for the Wadawurrung people to own and manage water on their country |

CCMA | WTOAC, DELWP, BW, CHW, BCC, GPS, MSC | |||||

| NOR3 | Encourage landowners to apply best practice land management by: 1) using property management planning; 2) use of Landcare networks; 3) actively researching and facilitating market drivers that promote sustainable ag/land management practices; and, 4) designing and delivering a comprehensive engagement program to support and empower farming communities |

CCMA | AgVic, DELWP, Landcare | |||||

| NOR4 | Best land management practices are also implemented across other Northern Uplands cohorts including agencies, developers, and the broader catchment community | CCMA | DJPR, PV, DELWP BCC, GPS, MSC | |||||

| NOR5 | Ensure development planning considers, minimises and where possible avoids adversely impacting floodplains, biodiversity, land and water assets including encouraging water sensitive urban design and use of integrated water management principles and requiring developers to: 1) protect and enhance native vegetation and habitat 2) protect and enhance floodplain function 3) protect cultural heritage |

BCC, GPS, MSC | CCMA, DELWP | |||||

| NOR6 | Enhance riparian management within priority waterways of the Northern Uplands as defined in the Corangamite Waterway Strategy | CCMA | BW, CHW, Landcare | |||||

| NOR7 | Develop an integrated masterplan for Kitjarra-dja- bul bullarto langi-ut (Barwon River Parklands) and implement high priority projects | CCMA | CoGG, BW, PV, Tourism Greater Geelong and the Bellarine, WTOAC, DELWP, GPS, G21, DHHS, SRV, BC | |||||

| NOR8 | Ensure the assessment of applications for new or transfers of groundwater entitlements in the Bungaree and Cardigan Groundwater Management Areas takes into account the impact of extraction on connected waterways and Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems (GDEs) | SRW | CCMA | |||||

| NOR9 | Explore and implement cost effective water efficiency measures including demand reduction initiatives and alternative water sources by implementing the following plans and strategies: 1) Central Highlands and Barwon Water Urban Water Strategies 2) priority projects identified by the Central Highlands and Barwon Water Integrated Water Management Forum; and, 3) relevant actions from the 2021 Central and Gippsland Sustainable Water Strategy |

CHW, BW | CCMA, DELWP | |||||

| NOR10 | Manage the current environmental water entitlement for the Moorabool River to maximise downstream benefit according to the recommendations of the Flows Study | CCMA | VEWH | |||||

| NOR11 | Investigate and implement opportunities to increase the environmental entitlement for the Moorabool River including implementing the outcomes of the 2021 Central and Gippsland Sustainable Water Strategy. | CCMA | BW, CHW, DELWP | |||||

| NOR12 | Identify opportunities for Cultural Burning and implement as appropriate | WTOAC | CCMA | |||||

| NOR13 | Ensure community education and engagement activities are grounded in the most recent and relevant social research available and target local demographics. | CCMA | DELWP, BCC, GPS, MSC, BW, CHW | |||||

| NOR14 | Encourage and enable community participation (volunteering) 1) in on-ground environmental works to restore and protect environmental assets 2) citizen science programs |

CCMA | Landcare, BCC, GPS, MSC | |||||

| NOR15 | Engage with the community on the need to mitigate and adapt to climate change and its impacts. | CCMA | DELWP, Landcare, BCC, GPS, MSC | |||||

| NOR16 | Action Plans are developed that leads to a 25% increase of non-government investment into the region to address high priority biodiversity actions | CCMA | DELWP, BCC, GPS, MSC, Landcare | |||||

| NOR17 | Develop best practice management actions to achieve an overall net gain of ‘Suitable Habitat’ for priority species by 2027 | CCMA | DELWP | |||||

| NOR18 | Implement additional areas of sustained predator, herbivore and weed control in priority locations, reflecting Biodiversity Response Planning outputs, Strategic Management Prospects and other regional plans | DELWP | CCMA, PV, Landcare, BCC, GPS, MSC | |||||